I’ve been holding my tongue on the issue of segregated schools (mostly because I’ve been wagging my tongue about one of the facilitators of segregated schools: charter schools), but after reading an article yesterday about mixed income housing complete with a back door for the lower income residents to use , the time for silence is over. Though I’ve never mentioned it in any blog posts, I’ve long been a proponent of mixed income housing. In graduate school, I did some research with Claire Smrekar on the HOPE VI project: a federal housing initiative to tear down low income communities and rebuild mixed income housing in the exact location. People who previously lived in the neighborhood are given priority for housing once the new construction is complete.

While I like the idea of mixed income for reasons I will explain in a second, I do not like the structure of the program(s). In summary, the neighborhood has a certain number of houses dedicated to different income groups. No, the lower income houses are not on separate streets, nor are they subpar compared to the higher income houses. Essentially, all the homes look the same, are the same size and have similar layouts. Higher income residents pay their mortgage and other bills the same way they would in any community. The lower income residents who qualify for housing assistance, have reduced rent and either all or some of their utilities covered. In exchange for living in such fancy digs however, there are tons of rules for residents (mostly the lower income residents) including: no cars parked on the street, no toys in the yard, the blinds must not be damaged, children cannot be outside after certain hours, once a month the neighborhood ‘manager’ comes to inspect how well you are caring for the home. Further, the residents receiving housing assistance must also meet one of the following criteria: be working at least part time, be enrolled in school full time, or be able to demonstrate (read: prove to the neighborhood manager) you are searching for employment. Finally, residents are required to attend workshops once a month about things like ‘money management’, ‘providing a safe environment for your children’, and ‘resume writing’. I don’t have to explain why I dislike all of the rules because it is fairly obvious. For those who’ve missed the problem here, I have two words: cultural whitening.

But moving on…I have long said that the most effective way we will reduce variability in quality/achievement across public schools is to ensure every public school serves an economically diverse student population. Here is why that matters: schools are funded primarily through property taxes. The only people who pay property taxes are people who own property. The people who own property tend to be middle and upper class, and white. Consequently, schools in locations where middle and upper class people live (and pay property taxes) are much better funded than schools in neighborhoods full of renters. What’s more is that wealthier parents are also those parents most likely to be highly educated themselves. They therefore have the cultural and social capital to know how the system works. In essence, they enact their power in a democratic social institution and force public schools to be good. Whether that’s through their participation in school leadership (Board of Education, PTO/PTA), through parental involvement, or through financial contributions, they make sure their children are receiving a quality education. If lower income and working class children were in schools with higher income children, they would [theoretically] reap the benefits of higher income parents’ advocacy.

So how do we make this happen in an era of income (and racially) segregated schools? Through mixed income housing. That way, the money homeowners pay in property taxes will go to the same schools their lower income neighbor’s children attend. Beyond school funding, I do believe the presence of middle class and high income families in a community would also change the local economic market. On one hand, when communities are gentrified, we see the disappearance of the mom and pop shops in favor of Whole Foods, Starbucks, and any trendy cupcake shop. I do not approve of this. But with a mixed income neighborhood, the hope is that the local small businesses, many of which are owned by neighborhood residents, can remain while also bringing in perhaps not mega chain stores, but instead, higher quality food sources, better access to healthcare, and more reliable public services (e.g., public transportation, parks, community centers). Let me be clear here, I am not in favor of ‘urban renewal’ (read: gentrification). I do not believe people should be displaced from their homes/communities. I do not believe neighborhoods should lose their history because people who do not live in that area think it’s ‘dangerous’. I do however believe in the power of money. I do believe that consolidated poverty is the root cause of many of the issues we see in lower income areas. What do you expect to happen when you put a lot of people with little resources in a confined space with almost no access to basic necessities like quality food, healthcare, or education? How do you expect them to succeed when you’ve set them up to be crabs in a barrel under a Darwin-esque regime of survival guised as meritocracy?

But I digress.

My actual point here is to outline the ways in which I am rethinking my solution of mixed income housing to solve the problem of inequitable school funding (and all its concomitants). I still believe everything I said about the value of mixed income housing; however, I am expanding my theory to include not just the context of schooling, but also the practices within schools.

I’ve never believed that racial integration would eradicate racism. That theory to me has always been illogical and flawed. Proximity doesn’t change attitudes; it leads to polarization and stronger identification with in-groups. INTERACTION changes attitudes. It really is a catch 22 because we know that between-group interactions lead to higher achievements (because of shared knowledge/skills), but we need teachers, policies, and school climates supportive of that interaction. Diversity means nothing if there are no relationships between diverse peoples.

Beverly Tatum made that clear in her classic text, Why are all the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? It is dangerous to believe that mixed income (and consequently, mixed race) schools will magically make everything better. It will not. Those attitudes will trickle into the classroom and before we know it, separate but equal will be WITHIN the schools, not BETWEEN schools. As we see in the article about mixed income housing in New York, those in power not only want to be in power, they want to be SEEN being in power. They want to FEEL in power. What does this mean for the schooling experiences of low income children? Will they be made to sit in the back of the classroom? Will they have separate lockers? Different teachers? We already know that even in the mixed race schools we do have, students of color are labeled special education and tracked into remedial courses at disproportionate rates. They are also suspended and expelled at rates three times that of white students. If this is the outcome of mixed income schools, I am pulling a Diane Ravitch. I rescind my support of mixed income housing and mixed income schools. I’d rather my child be in an underfunded school with fewer resources than be treated like an outcast in a well-funded school. I can supplement my child’s education, but I can’t repair my child’s broken spirit.

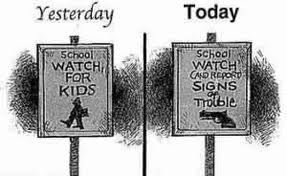

This is not a choice I or any parent should have to make. When will we wake up from the reality that we are sleepwalking back to Plessy?

You must be logged in to post a comment.